Lilly Loise Culp Hogan, UT’s oldest living alumna, passed away on November 19, 2023. The Office of Alumni Relations celebrated Lilly’s legacy a few years ago on her 100th birthday and is honored to have been a part of this Vol’s extraordinary life. In lieu of flowers, the family requests that donations be made to the Hogan Family Scholarship Endowment.

Loise Culp Hogan (’49) grew up on a family farm in the Great Depression, decoded for Naval Intelligence in World War II, came to UT with her husband on the GI Bill, raised four children, and still dresses in orange to watch the Vols.

Lilly Loise Culp was born on February 5, 1920, the next-to-last of 11 children of family farmers Monroe and Lilly Culp in the rural Ebenezer community near Hornbeak, nestled between Reelfoot Lake, Troy, and Union City in the Northwest corner of Tennessee. They raised corn, sweet potatoes, and beans, and kept chickens, pigs and cows, and enjoyed occasional trips to Reelfoot Lake for picnics and swimming.

Life on the Culp farm included barn dances, where piano and fiddle music drew neighbors from all over Obion County. A well-to-do aunt in Middle Tennessee provided the family with parcels of beautiful clothes, which Lilly deconstructed and then crafted into clothes for all the children. The Culp girls learned to sew, making their own patterns, and gained an appreciation for fabrics, textures, colors, and clothing design.

Until eighth grade, Culp attended the Ebenezer School, a one-room schoolhouse, where her teacher was her oldest sister, Zora. Culp’s goal was to beat out a male classmate for the best grades, especially in math, her strongest subject. She remembers Zora driving up in the first automobile she ever saw.

In high school, Culp’s older brother Fred walked her to the Dixie School, midway between Hornbeak, Troy, and Union City. Occasionally their father would let them ride the horse to school, and it was stabled in a barn attached to the school.

Lilly Loise Culp was born on February 5, 1920, the next-to-last of 11 children of family farmers Monroe and Lilly Culp in the rural Ebenezer community near Hornbeak, nestled between Reelfoot Lake, Troy, and Union City in the Northwest corner of Tennessee. They raised corn, sweet potatoes, and beans, and kept chickens, pigs and cows, and enjoyed occasional trips to Reelfoot Lake for picnics and swimming.

Life on the Culp farm included barn dances, where piano and fiddle music drew neighbors from all over Obion County. A well-to-do aunt in Middle Tennessee provided the family with parcels of beautiful clothes, which Lilly deconstructed and then crafted into clothes for all the children. The Culp girls learned to sew, making their own patterns, and gained an appreciation for fabrics, textures, colors, and clothing design.

Until eighth grade, Culp attended the Ebenezer School, a one-room schoolhouse, where her teacher was her oldest sister, Zora. Culp’s goal was to beat out a male classmate for the best grades, especially in math, her strongest subject. She remembers Zora driving up in the first automobile she ever saw.

In high school, Culp’s older brother Fred walked her to the Dixie School, midway between Hornbeak, Troy, and Union City. Occasionally their father would let them ride the horse to school, and it was stabled in a barn attached to the school.

Fred’s carefree approach to school led his father to pull him from school in 11th grade to work on the farm. He continued to walk his sister to school, and she coached him on high school subjects. She graduated in 1938 as valedictorian and, thanks to her tutoring, Fred graduated with her as salutatorian.

After high school, Culp and her sister Kitty rented an apartment in nearby Union City, where Culp sewed the seam—always the same seam—at a shirt factory. In 1938, their landlord, Bessie Woods, introduced Culp to a cousin, Reed Hogan, who was on leave from the US Navy. He had been born across the Mississippi River in Braggadocio, Missouri, moved to the Hornbeak area as a child, and graduated from high school there before joining the Navy and shipping out on the USS Texas. Culp remembers noticing immediately how handsome he was. On their first date, they went to a movie in nearby Troy, then afterward “sat on the front porch swing and talked and talked and talked,” as she recalls it.

After high school, Culp and her sister Kitty rented an apartment in nearby Union City, where Culp sewed the seam—always the same seam—at a shirt factory. In 1938, their landlord, Bessie Woods, introduced Culp to a cousin, Reed Hogan, who was on leave from the US Navy. He had been born across the Mississippi River in Braggadocio, Missouri, moved to the Hornbeak area as a child, and graduated from high school there before joining the Navy and shipping out on the USS Texas. Culp remembers noticing immediately how handsome he was. On their first date, they went to a movie in nearby Troy, then afterward “sat on the front porch swing and talked and talked and talked,” as she recalls it.

When Hogan returned to the Navy, he joined the 2nd Battalion Raiders, known as Carlson’s Raiders, a special-ops Marine unit. After Pearl Harbor, they were deployed in the South Pacific and fought in some of the bloodiest battles. He also served with the 1st Battalion of the Marines during his active duty.

Tired of sewing the seams of shirts, Culp set out to join her brother Calvin in De Pere, Wisconsin, where he was a photographer. In his studio, she learned to take, print, and colorize photos. During this time, she and Hogan wrote to each other constantly, even though mail service to his areas of service was patchy, sometimes intercepted by the enemy and heavily censored by the Navy. The positions and circumstances of his Battalion were considered top secret and crucial to strategic efforts during the war.

As the war intensified, Culp decided to join the Navy. As she tells it, her dream was to be a wartime photographer, but during the intake process, her math skills were discovered, and the Navy decided that they needed her in a different role—decoding enemy messages (cryptology) in Naval Intelligence.

Investigators were sent to the Hornbeak area to assess her for top security clearance. Culp did not know that was happening until later when her mother wrote that “there were folks all over town asking about Lilly Loise Culp’s character, reliability, and honesty.”

After basic training, she was assigned to barracks, WAVE Quarters D, in Washington, DC, and worked in an underground facility in Alexandria, Virginia, near where the Pentagon was being constructed. “She tells of round-the-clock work by women trying to decode the enemy messages that would provide clues to our military regarding best use of resources,” says her daughter, Mary Beth Hogan (’97). “Casualties mounted and many men were lost daily. It was a time of great stress. Loise and all women who helped with the effort not only saved many lives but helped win the war.” Culp continued photography while in the Waves and won an award for a particularly great picture of Waves in front of the US Capitol building.

Tired of sewing the seams of shirts, Culp set out to join her brother Calvin in De Pere, Wisconsin, where he was a photographer. In his studio, she learned to take, print, and colorize photos. During this time, she and Hogan wrote to each other constantly, even though mail service to his areas of service was patchy, sometimes intercepted by the enemy and heavily censored by the Navy. The positions and circumstances of his Battalion were considered top secret and crucial to strategic efforts during the war.

As the war intensified, Culp decided to join the Navy. As she tells it, her dream was to be a wartime photographer, but during the intake process, her math skills were discovered, and the Navy decided that they needed her in a different role—decoding enemy messages (cryptology) in Naval Intelligence.

Investigators were sent to the Hornbeak area to assess her for top security clearance. Culp did not know that was happening until later when her mother wrote that “there were folks all over town asking about Lilly Loise Culp’s character, reliability, and honesty.”

After basic training, she was assigned to barracks, WAVE Quarters D, in Washington, DC, and worked in an underground facility in Alexandria, Virginia, near where the Pentagon was being constructed. “She tells of round-the-clock work by women trying to decode the enemy messages that would provide clues to our military regarding best use of resources,” says her daughter, Mary Beth Hogan (’97). “Casualties mounted and many men were lost daily. It was a time of great stress. Loise and all women who helped with the effort not only saved many lives but helped win the war.” Culp continued photography while in the Waves and won an award for a particularly great picture of Waves in front of the US Capitol building.

In 1944, Hogan was wounded, received a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star, and was sent stateside. He and Culp were married by a justice of the peace in Arlington on March 16, 1944. Their honeymoon trip was to Niagara Falls followed by Nashville, Tennessee.

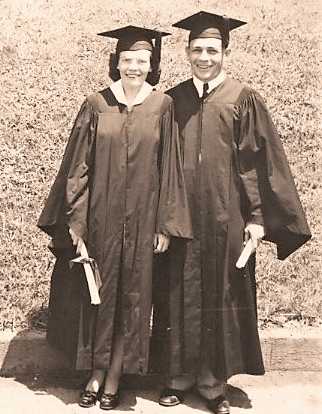

After the war ended, they both enrolled at UT on the GI Bill and graduated in 1949. Her degree was in business education. His was in business administration. Mary Beth says, “Mother recalls that a true highlight of their time together at UT was going to football games, she in the female section, he in male section. Loise tells that ‘There weren’t many married couples attending the same class and when we were in the same class, we always competed to see who could get the best grades. Sometimes the instructors kidded around with us in class about that.’ While at UT, Loise became known as ‘legs Hogan,’ a nickname that has persisted over time, even at age 100! She attributes that to ‘all the climbing and walking I did to make my classes on the UT campus.’”

After the war ended, they both enrolled at UT on the GI Bill and graduated in 1949. Her degree was in business education. His was in business administration. Mary Beth says, “Mother recalls that a true highlight of their time together at UT was going to football games, she in the female section, he in male section. Loise tells that ‘There weren’t many married couples attending the same class and when we were in the same class, we always competed to see who could get the best grades. Sometimes the instructors kidded around with us in class about that.’ While at UT, Loise became known as ‘legs Hogan,’ a nickname that has persisted over time, even at age 100! She attributes that to ‘all the climbing and walking I did to make my classes on the UT campus.’”

Hogan went on for an MPA at Wayne State in Detroit, continuing his service in the US Naval Reserves until 1955. Culp worked in the dean’s office. In 1950, he was offered a job as administrator of a new hospital in Union City. Mary Beth, the oldest, was born there in 1951. In 1952, Hogan was offered a position to oversee the construction and opening of a new hospital in Clarksdale, Mississippi. Their son Reed Jr. was born in 1955, Jeannie in 1960, and Kim in 1963.

Sadly, Hogan died of a massive heart attack in 1964. He was 44. His wife raised the children as a single mother. “She and my dad both believed in the value of education,” says Mary Beth. “As a young widow, she instilled that in all four of her children, all of whom have terminal degrees.”

Mary Beth earned her PhD in community health from UT in 1987 and teaches at Fayetteville State in North Carolina. Reed Jr. is a gastroenterologist in Jackson, Mississippi. Jeannie Sansing is an attorney in Oxford, Mississippi, and Kim Pesaniello is a psychiatrist in Snow Hill, Maryland.

Sadly, Hogan died of a massive heart attack in 1964. He was 44. His wife raised the children as a single mother. “She and my dad both believed in the value of education,” says Mary Beth. “As a young widow, she instilled that in all four of her children, all of whom have terminal degrees.”

Mary Beth earned her PhD in community health from UT in 1987 and teaches at Fayetteville State in North Carolina. Reed Jr. is a gastroenterologist in Jackson, Mississippi. Jeannie Sansing is an attorney in Oxford, Mississippi, and Kim Pesaniello is a psychiatrist in Snow Hill, Maryland.

In 1994, Culp moved into the Armed Forces Retirement Home (AFRH) in Gulfport, Mississippi. During Hurricane Katrina, she elected to remain in the building. After being urged to leave and stay with one of her children, she opted to stay in the building with other residents and staff. Indicative of her adventuresome spirit, her rational was: “I’ve never seen a hurricane before.” The waters rose 30 feet to the building’s third floor. Along with her close friend and other residents, they were rescued by Seabees after the storm surge receded. “Next time, I’ll evacuate,” she says. Ultimately, they were relocated to a sister facility in Washington, DC, until the AFRH was rebuilt.

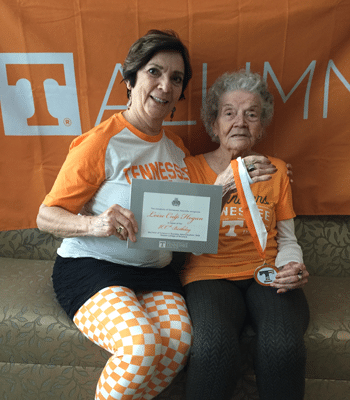

She has seven grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren, is in good health, has all her mental faculties, and loves wearing orange UT shirts while watching games on TV. “They remind me of when Reed and I went to the games. It was our favorite thing to do together while we were there!”

She has seven grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren, is in good health, has all her mental faculties, and loves wearing orange UT shirts while watching games on TV. “They remind me of when Reed and I went to the games. It was our favorite thing to do together while we were there!”

On February 5, her family gathered in Gulfport to celebrate her 100th birthday. She was presented with a UT military coin and a centennial certificate signed by Associate Vice Chancellor for Alumni Affairs Lee Patouillet.

“Loise Culp Hogan exemplifies the Volunteer spirit,” wrote Patouillet. “We thank her for her service to our country. And we congratulate her on reaching this remarkable milestone!”

She often says, “I’ve had a wonderful life. It’s been a really great ride!”

“Loise Culp Hogan exemplifies the Volunteer spirit,” wrote Patouillet. “We thank her for her service to our country. And we congratulate her on reaching this remarkable milestone!”

She often says, “I’ve had a wonderful life. It’s been a really great ride!”